Andy Nicholls, Statistics Director, Head of Statistical Data Sciences, GSK

Paulo R. Bargo, Director Scientific Computing, Statistics & Decision Sciences, Janssen R&D

John Sims, Director, Analytical Systems Architect & Data Science - Pfizer Vaccine Research

On behalf of the R Validation Hub, an R Consortium-funded ISC Working Group

January 23, 2020

View and/or download the PDF version of this white paper here.

1. Scope and Background

This white paper addresses concerns raised by statisticians, statistical programmers, informatics teams, executive leadership, quality assurance teams and others within the pharmaceutical industry about the use of R and selected R packages as a primary tool for statistical analysis for regulatory submission work. When discussing validation of software systems two areas should be considered:

- Infrastructure validation

- Software validation

Infrastructure includes the server, OS, necessary infrastructure software, etc… For example, a system may use a server running Redhat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) version 6 and several other infrastructure software pieces including proxy servers like Apache httpd. Documenting infrastructure (or the environment) is an essential part of the validation process and this validation could follow standard practices such as those proposed in GAMP5, particularly change control management. Discussions regarding infrastructure validation are not in scope of this paper.

The aim of this paper is to propose a possible risk-based approach for assessing R package accuracy within a validated infrastructure.

Many of the thoughts and ideas addressed in this paper are extracted, verbatim, from the R Validation Hub, a cross-industry initiative whose mission is to enable the use of R by the bio-pharmaceutical industry in a regulatory setting.

The paper reflects the current thinking of the R Validation Hub working group and may evolve over time. Additional detail will be provided via the website and future papers.

2. What is R?

As stated on the R-Project website and the guidance for the use of R in regulated clinical trial environments, “R is a language and environment for statistical computing and graphics… It is available as Free Software under the terms of the Free Software Foundation’s GNU General Public License in source code form.” The official R distribution consists of ‘Base R’ and ‘Recommended Packages’. Each of these is a collection of R packages (code libraries) that can be defined as follows:

- Base R - base, compiler, datasets, graphics, grDevices, grid, methods, parallel, splines, stats, stats4, tcltk, tools, utils

- Recommend Packages - boot, class, cluster, codetools, foreign, KernSmooth, lattice, MASS, Matrix, mgcv, nlme, nnet, rpart, spatial, survival

Beyond official R distribution, users in the open source community can submit their own R packages to an open source package repository known as the Central R Archive Network (CRAN). There are currently over 15,000 packages available on CRAN, with further packages available via another popular life sciences repository (Bioconductor), GitHub and a scattering of other websites. In addition, R packages are sometimes developed for internal use.

3. Regulations Governing the use of Statistical Software

In 1997, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued 21 CFR Part 11 to provide regulations for electronic records and signatures. This final ruling states that:

“\[Electronic records and signatures\] be trustworthy, reliable, and generally equivalent to paper records and handwritten signatures executed on paper.”

Then in 2003, the FDA released the Guidance for Industry: Part 11, Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures – Scope and Application. This guidance clarifies how Part 11 should be enforced, and the intended scope.

Broadly, there are two types of applications:

- Transactional – applications that collect data and often require electronic signature

- Non-transactional - used for decision support and/or reporting

R tends to fall more in the ‘non-transactional’ space and as such, 21 CFR Part 11 typically does not apply. In 2015, the FDA released a Statistical Software Clarifying Statement. This document states that they do not require the use of any specific software for statistical analyses. But, the FDA requests that software package(s) be documented upon submission. This documentation must include version and build identification. In conclusion, 21 CFR Part 11 is not relevant or mandatory in the context of statistical analysis software itself. However, when using R as part of a validated system, elements of 21 CFR Part 11 do apply. The guidance for the use of R in regulated clinical trial environments provided more details of this topic. The rest of this paper focuses on R package validation and its dependency.

4. R Packages and Validation

According to the FDA’s Glossary of Computer System Software Development Terminology:

“Validation: Establishing documented evidence which provides a high degree of assurance (accuracy) that a specific process consistently (reproducibility) produces a product meeting its predetermined specifications (traceability) and quality attributes.”

In pharmaceutical development, validation typically refers to systems validation. The system validation should incorporate all of the following elements:

- Accuracy

- Reproducibility

- Traceability

This paper outlines how to ensure the accuracy of R packages when used as part of a validated environment with R.

Note: Since R is open source, ensuring that the environment is reproducible and traceable presents several challenges. These challenges should be addressed by end user’s organisation.

4.1. Accuracy

When assessing the accuracy of R packages, the R Validation Hub differentiates R packages by the following types (see German et al, 2013i):

- base and recommended (core) packages - developed by the R Foundation and shipped with the basic installation

- contributed (open source) packages - developed by anyone, and may differ in accuracy

Figure 1 - Source: German et al (2013): The Evolution of the R Software Ecosystem (German, 2013)1

Core packages and contributed packages are managed by different processes. Therefore, different requirements are needed to ensure that both types of packages reliably produce accurate results.

4.1.1. Base R and Recommended Packages

The R Foundation develops both the base and recommended packages and follows a software development life-cycle that ensures the accuracy of each. These practices include:

- Proper maintenance of the R source code, and control of releases

- Testing the software and identifying issues for the Core Team to address

- The R Core Team hiring highly qualified individuals

- Validation testing each R release against known data and known results, and resolving all errors prior to release

The R Foundation provides context and further information around each of these points in R: Regulatory Compliance and Validation Issues. A Guidance Document for the Use of R in Regulated Clinical Trial Environments.

In addition to the steps taken by the R Foundation and R Core Team to ensure the validity of Base R and Recommended packages, the R user community plays an important role in ensuring that the code is accurate. The R Foundation monitors feedback from users by the r-devel e-mail list and the R bug tracking system. This process allows for more extensive testing, and increases the likelihood that bugs are fixed before releases.

In conclusion, there is minimal risk in using base and recommended (core) packages as a component in a validated system for regulatory analysis and reporting with R.

4.1.2. Contributed Packages

Since R is Open Source, contributed packages can be developed by anyone and may depends on other R package and softwares. Therefore, ensuring the accuracy of each contributed package and its dependency is necessary.

R Validation Hub focuses on contributed packages on The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). All packages available on CRAN have passed a series of technical checks, as outlined in the checklist for CRAN submission. The technical checks for an R package ensure that:

- all the code examples run successfully

- all the package tests pass

- the package is compatible with other packages on CRAN

However, these checks do not necessarily guarantee the accuracy of an R package. It is therefore suggested that a risk assessment exercise be conducted to evaluate the likely accuracy/validity of an R package with respect to its intended use.

4.2. Reproducibility

It is important to acknowledge that R (like other open source languages) presents additional challenges with respect to the reproducibility of an environment. The evolution of R packages is effectively continuous and thus maintaining a stable R installation that allows for the addition of new and/or updated packages can be a challenge.

Package dependency trees can be very large and complex with potential system dependency. A single package may ultimately require the installation of over 100 additional packages and other software. If just one package version number turns out to be incompatible the Intended for Use package of interest cannot be installed. It is therefore vital to ensure compatibility of R packages within an installation. It should be noted that on any given day all such dependencies on CRAN have been resolved. However, there is no standard way of ensuring compatibility between repositories such as CRAN and Bioconductor or GitHub. Some R packages also have system dependencies which need to be managed.

There are several commercial and open source offerings that attempt to deal with the management of R packages in different ways. Some of these focus on R, some on the environment itself. These are not discussed here.

4.3. Traceability

One of the core concepts presented in this paper is that Imports are not typically loaded by users and need not therefore be directly risk-assessed. If adopting this risk-based approach then measures need to be taken to ensure that users do not directly load the Package Imports. It is suggested that this is handled mainly through process, although tools could be developed to check using sessionInfo or devtools::session_info that check the loaded packages against packages lists of Intended for Use and Imports. In any case the use of these tools within a standard, logged, workflow is highly recommended to ensure traceability of the work.

5. System Qualification

A system qualification typically includes the execution of Installation, Operational and Performance tests. To qualify a system based around on R, tests need to be written to ensure that the R installation has been installed correctly and that it performs as expected. This activity is required for the overall installation, regardless of the risk assessment score for individual packages.

The purpose of the system qualification is to ensure the reproducibility of expected results. It is not to reassess the risk of individual packages.

Some packages may already contain tests. All such tests are suitable for a system qualification. However, it should be noted that the expected results, as determined by package authors / maintainers, may occasionally differ depending upon the Operating System configuration. It may not therefore be prudent to simply re-run all available tests. Instead, a subset of tests could be chosen that reflect typical usage.

6. A Proposed R Package Risk Assessment Framework

6.1. Classifying R Packages within an Installation

Users typically ‘load’ a package to access the functions and other objects stored within it. Some of the functions within the loaded package may, in turn, call functions within other packages. But a user would not load, nor call the functions within these packages directly2.

Within an installation, two classifications of R packages are proposed:

- Intended for Use. These will be loaded directly by a user during an R session.

- Imports. These packages are required to be installed in order to use the Intended for Use packages. They are comparable to a system dependency, or the ‘back-end’ code supporting a user interface.

An Intended for Use package may also be an Import for another package. In such cases a conservative approach should be adopted and the package should be classified as Intended for Use. Imports are identified within a package’s ‘DESCRIPTION’ file using the ‘Imports’ field. This field differs from the ‘Depends’ field for which dependencies are imported into the name space. This allows the end user to use the functions contained within the package. Packages specified in the depends field should therefore be classified as Intended for Use packages.

A risk-based approach should focus on the way that components of the system will be used. From a reproducibility perspective, it is important that the Imports are managed appropriately. But, the accuracy of these packages only needs to be verified by assessing the Intended for Use packages. This approach can be extended to system qualification. During which, the operational focus should be on the Intended for Use packages and not the Imports. It is also important to make this distinction when considering the maintenance of a system over time

6.2. Components of a Risk Assessment Framework

A risk assessment framework should evaluate R packages based on four criteria:

- Purpose

- Maintenance Good Practice (Software Development Life Cycle)

- Community Usage

- Testing

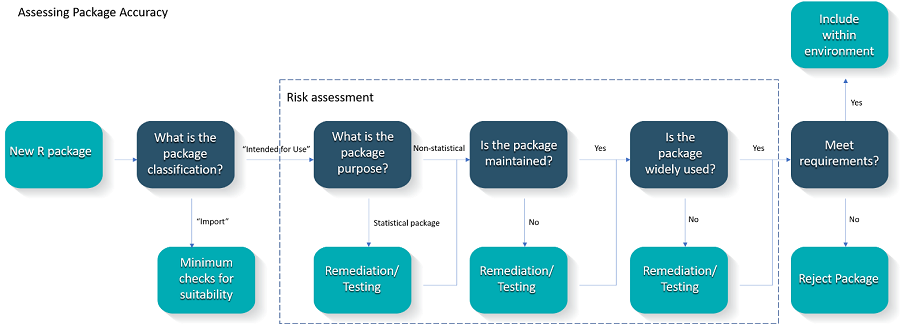

The criteria are described in more detail in the following subsections and additional information on the proposed metrics, the rationale for their use and how these are being implemented can be found in the R Validation Hub website. An overview of the proposed process is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Proposed Validation Workflow

It is recommended that the risk assessment be collated via individual package reports. These reports should detail the level of risk that each package presents. Justification for these scores should be based on the metrics obtained for the package. These reports may serve as documented evidence of the accuracy assessment for R.

6.2.1. Purpose

The purpose of an R package and its intended use greatly impacts the level of risk presented by the package.

For simplicity, two classifications are proposed:

- Statistical

- Non-statistical

The ‘Statistical’ classification refers to any package that implements statistical/machine learning algorithms, even if that is not the primary purpose of the package.

Statistical packages present a greater degree of risk than non-statistical packages. This is because the primary or secondary statistical analysis for a study might be based upon statistical models. Also, the complexities of the algorithms underpinning the main routines can make bugs difficult to detect. A package aimed at, say, data manipulation may have just as big an impact but errors would be much easier to identify and therefore more likely to be detected when the package has been exposed to extensive community testing.

Non-statistical packages could be divided into further categories, for example:

- Data wrangling / Transformation / Manipulation

- Data Input / Output (file systems, external documents (e.g. excel), databases (e.g. RDBMS’ such as Oracle, PostgreSQL, and MySQL

- Communication (knitr, rmarkdown)

- Modelling (non-statistical)

- Application Interface (e.g. Shiny Server Pro)

Organisations may choose to further adapt their approach to risk assessment and testing based on these, or other, finer level classifications.

6.2.2. Maintenance Good Practice

Adopting best practices to manage the software development life-cycle can significantly reduce the potential for bugs / errors. Package maintainers are not obliged to share their practices (and rarely do). However, the open source community provides several ways of measuring best practice. The R Validation Hub website proposes some metrics to consider along with a rationale for why the metric is important in assessing package quality and risk.

Metrics may include whether the package has a vignette, website, news feed or formal mechanism for bug tracking, whether the source code is publicly maintained, the release rate for new versions; the size of the code base; author reputation and type of license.

6.2.3. Community Usage

The user community plays an important role in open source software development. The more exposure a package has had to the user community, the more ad-hoc testing it has been exposed to. Over time the better packages tend to rise to the top of the pack, leading to more downloads and increased exposure.

The aim of the community usage metrics is to assess the level of exposure to the wider community and thus the level of risk that a package presents. Community usage could be assessed through metrics such as the package (and version) maturity; whether the package is available through a standard repository; reverse package dependencies; number of downloads.

6.2.4. Testing

Testing is a vital component in a well-established Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC). As a genertal rule, the more tests a package has, the more confident one can be in the stability of the package over time. Packages should include unit tests, embedded within a standard unit-testing framework. For such packages a code coverage metric can be calculated and compared with package norms.

6.3. Determining Risk

Although each package metric is a numeric measure, the scales are very different. It would be possible to turn these into an overall risk score, but this score might be somewhat opaque to anyone reviewing the assessment for the first time. Instead it is recommended that the metrics form part of a subjective assessment made by a qualified individual and reviewed by a similarly qualified colleague.

Each of the four criteria should be assessed separately before combining for an overall assessment of risk for the package. It is not within the scope of this paper to fully identify appropriate qualifications but clearly the assessor and reviewer should be of a suitably high grade and have experience of statistical programming with R. When assessing a Statistical package, it is important to understand the nuances of the model(s) being implemented. The risk assessment of a statistical package should therefore be performed by a Statistician with an appropriate level of experience in their field.

6.4. Responding to Risk

The risk classification can be used to determine:

- Whether the package is included as part of the R installation within the validated system

- The extent of additional remediation / testing required to mitigate any risk

If a package is not included as part of a validated system, then by implication it is not approved for use within the controlled environment. If the environment permits a user to install their own packages the onus would be on the user to take extra precautions to ensure that it behaves as expected for their specific use case. In all cases, it is expected that users would follow their internal Quality Assurance Standard Operating Procedures.

6.4.1. Package Remediation / Testing

One way of mitigating risk for higher risk packages is to generate tests for important package functionality. The process for this should be no different than the standard process for developing functions/macros internally. Typically, requirements would be gathered, and tests written against each requirement such that any test could be traced back to a requirement. It is recommended using a unit test framework such as testthat to implement this in R.

Tests should be written for all statistical modelling functions within an Intended for Use Statistical Package, regardless of the risk assessment. Any tests generated can be used to assist in the qualification of a system.

Care should be taken when testing statistical packages to ensure that a pass/fail result can be achieved. Known results from literature are typically the best reference for testing complex statistical procedures. It may be sufficient to use existing tests within the package if these are deemed appropriate by the package assessor. It may sometimes be appropriate to test against known results from other software, provided both R and the comparison software claim to implement exactly the same method.

In a risk-based framework, the lower risk packages will typically have been developed according to best practices and/or been subjected to a high degree of community testing. Additional remediation for such packages is unlikely to yield any significant reduction in risk.

6.5. Vendor Assessments and Trusted Resources

For proprietary software it is common to perform vendor assessments / audits to explore the internal validation practices of the vendor. If a company is satisfied with the internal validation practices of the vendor, they may designate the vendor a ‘trusted’ status. The impact of this might be that any software produced by that vendor is deemed to be low risk.

For open source software such audits are not logistically feasible. However, based on information available in the open source domain, it may still be possible to perform a virtual audit of a vendor and their practices. For example, R Foundation and R Core team, have published information about their practices in R: Regulatory Compliance and Validation Issues. A Guidance Document for the Use of R in Regulated Clinical Trial Environments. It is the opinion of the R Validation Hub that this is sufficient to allocate the R Foundation a trusted status. This would render the collection of Base R and Recommended packages low risk as a result.

6.5.1. Becoming a Trusted Resource

Over time, some patterns will likely emerge from continued risk assessments. In particular, certain package authors and maintainers may become associated with low risk packages. It would be reasonable to allocate a trusted status to any package developer that attains a ‘low risk’ evaluation for multiple packages over a sustained period of time. Precisely how many packages, and how many iterations of risk assessment should be completed before allocating the Trusted Resource status, is down to the individual organisation to determine.

There are several popular packages / collections of R packages that could be considered for a ‘trusted resource’ status. One of the most popular examples is the tidyverse, as described in the following section.

6.5.2. An Example of a Possible Trusted Resource: The tidyverse

The tidyverse is a commercially supported collection of contributed R packages. According to https://www.tidyverse.org/:

“The tidyverse is an opinionated collection of R packages designed for data science. All packages share an underlying design philosophy, grammar, and data structures.”

The tidyverse is primarily developed by a team at RStudio who have publicly shared the set of Design Principles via an online book. These are used by the tidyverse team to “promote consistency across packages in the core tidyverse”. The same team have also published a tidyverse style guide.

Given the available documentation, the consistency and popularity of the tidyverse, and the commercial backing of the project by RStudio, there is a reasonable case to consider the tidyverse team a trusted resource.

7. Summary

When using R as part of a validated system, elements of 21 CFR Part 11 do apply, although the regulation is not directly applicable to programming languages. Systems validation focuses on accuracy, reproducibility and traceability of the system. For R the primary challenge is in ensuring the accuracy of results.

A risk-based approach to the adoption of R packages is highly recommended. This should focus on Intended for Use packages and not Imports. It is important to assess individual packages based on:

- Purpose

- Maintenance Good Practice

- Community Usage

- Testing

Using the metrics suggested in this paper it is possible to assign levels of risk to each of these elements to develop an overall risk classification for a package. The risk assessment should be documented by individual package reports. Additional remediation for low risk packages is unlikely to yield any significant reduction in risk. However, remediation in the form of tests, linked to user requirements, may be deemed necessary for higher risk packages.

Over time, collections of packages may obtain a ‘trusted’ status such that future offerings default to a low risk score without the need for a full risk assessment.

Regardless of the relative risk posed by a package, it is important to develop a set of qualification tests for Intended for Use R packages. These should be developed using a known framework such as ‘testthat’ and need not include all available tests within the packages themselves. Having established the accuracy and integrity of R packages within an installation, attention should be paid to the long-term maintenance of the system with respect to the additional challenges that R presents regarding reproducibility and traceability requirements.

<br>

German, D.M. & Adams, Bram & Hassan, Ahmed E.. (2013). The Evolution of the R Software Ecosystem. Proceedings of the Euromicro Conference on Software Maintenance and Reengineering, CSMR. 243-252. 10.1109/CSMR.2013.33.↩︎

It is worth noting that it is technically possible to call any function from any installed package but this is extremely rare behaviour within an analysis workflow.↩︎